Women Are Socially Constructed.

Though we are all human at birth, what does being a woman (or a man) mean? This blog explores the hypothesis that, despite their seeming naturalness, society may significantly influence these categories more than biology.

The Performance of Gender:

According to social constructionism, gender encompasses more than just biological sex (male or female); it also refers to the roles, practices, and social expectations that society assigns.

As Simone de Beauvoir stated, these concepts are acquired, not born. Often quoted in gender studies, her exact words were, “One is not born, but becomes a woman”

If nurturing were regarded more highly than strength, would the stereotypical characteristics of “manly” behaviour be connected with that favoured role?

This flexibility implies that our concepts of gender and masculinity are products of culture. There is historical proof of these shifting sands. It’s possible for a career that was once thought of as “women’s work” to become a “manly” one today (think mechanics or doctors).

Gender roles are expected to differ significantly throughout civilisations. Can these responsibilities be considered biological imperatives if they are not set and vary with time and location?

Going Beyond the Binary:

It also challenges the idea of a rigid dichotomy (man/woman). Many cultures acknowledge more than two genders, and some individuals identify in ways that defy the binary entirely.

The Hijras in India are considered a third gender with a rich history and cultural significance. The Bugis people of Indonesia have five genders. The Fa’afafine in Samoa are individuals assigned male at birth who identify with more feminine roles; the list goes on and on—it’s just that in Western culture, we have the hang-up of “the binary.”

This emphasises even more the possibility that gender identity is a continuum influenced by social experience and neurobiological factors.

Does this imply that biology is unimportant?

Biology determines a person’s sex (male or female), but society and other factors shape how we exhibit and interpret these differences. Although we may be born with certain predispositions, our environment shapes how we perceive and respond to those predispositions.

Acknowledging gender as a social construct can challenge limiting prejudices. It enables people to express themselves honestly without regard to what society thinks or feels. It can also aid in the eradication of bias and the creation of a more just society.

Try the hair test.

As you drive, check out who is driving the vehicle coming towards you. Initially, we often determine the driver’s sex not by their genitals (which we obviously can’t see) but by the length of the driver’s hair. As the oncoming vehicle gets closer, we may change our minds, and sometimes we are left undecided.

But if you think the hair test is inconclusive because perhaps many women have short hair, some men have long hair or no hair at all – the hair test works up close in everyday society.

Heather Fisher was an England rugby union player until she announced her retirement in 2021 – she has a constant problem of being identified as a man because she suffers from severe alopecia. In an emotional interview with Sky News, she talked about her experiences and being viewed by society as trans.

In another interview with the BBC, Heather says she “dreads” using public toilets because she is frequently mistaken for a man.

Ultimately, we decide people’s sex by how they look. We will immediately identify them as men if they have a beard, muscles, and a deep voice. Equally, if they wear a dress and look pretty, that’s a woman.

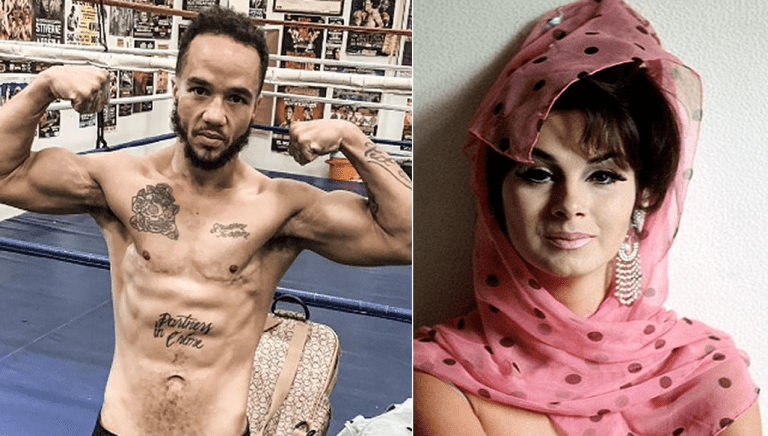

As I have shown in this blog, looks can be deceiving. To reinforce my points, yes, the image of the boxer in this article—he was assigned female at birth, and the woman you see was born a man.

So, next time you encounter a woman’s resilience or a man’s vulnerability, remember—they are not given; they are the brushstrokes of our shared masterpiece of diversity.

Moreover, how people present is how we initially identify them as men or women, and we make that decision based on social constructionism.

In short, adult human females are not necessarily identifiable as women; we can and do recognise some as men, or somewhere in between of the stereotypes in our binary culture – and all the Posie Parker rallies and Sex Matters legal cases to define women by sex won’t change that.

Social constructionism is here to stay.

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behaviour or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behaviour or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.